Saturday, December 24, 2011

Michael Eisen on censoring dangerous knowledge

Philosophical Diquisitions on Enhancement Technology

Friday, December 23, 2011

What Republicans don't get about racism

Most Republicans recognize that "racism is wrong", but it is the wrong sort of "wrong". They think of it as an intellectual error. Or a type of meanness. Either way, they think of it as a failure of the individual who is racist. They ignore any social aspects of racism more profound than self-segregation. They ignore that racism is fundamentally a political ideology, justifying the oppression of some people by others. They ignore that its continued prevalence is a social failure, not just a personal failure.

Most Republicans have internalized the conclusion that racism is "very wrong", but they way they apply this conclusion illustrates that they still don't get it. They still focus on the individual expressions of racism, while ignoring the social structure behind it. If one black racist acts threatening towards a white guy, they throw a fit and then get all self-righteous when the traditional anti-racist coalitions don't see it as anything more important than regular street crime. Republicans do this because they don't see the political nature of racism, and they can't distinguish between racism that is politically impotent (i.e. black racism) and racism that could lead to tyranny (i.e. white racism).

This is the stuff that Ron Paul doesn't get about racism, and why he too often tolerates the company of racists (e.g. the people who wrote his newsletters and his 2008 anti-Latino advertisements) -- he doesn't get how these individual acts fit into a larger system of oppression.

For more thoughts on related issues, see Gary Chartier's summary of the relationship between "left-wing market anarchism and Ron Paul"

Wednesday, December 21, 2011

When knowledge is dangerous

For the first time ever, a government advisory board is asking scientific journals not to publish details of certain biomedical experiments, for fear that the information could be used by terrorists to create deadly viruses and touch off epidemics.

In the experiments, conducted in the United States and the Netherlands, scientists created a highly transmissible form of a deadly flu virus that does not normally spread from person to person. It was an ominous step, because easy transmission can lead the virus to spread all over the world. The work was done in ferrets, which are considered a good model for predicting what flu viruses will do in people.The intent of the "authorities" (both scientific and legal) seems to be that the details of these experiments be restricted, so that only "legitimate scientists" have access to the information needed to replicate the experiments. I'm torn on this issue: clearly we don't want to hand a weapon of mass destruction to a homicidal maniac, but this restriction on scientific communication could usher in its own problems.

I don't have a clear thesis to argue for, so I just want to list a number of points that need to be considered while debating this decision:

- The scientific establishment (epitomized by the journals Nature and Science) wants to maintain its independence from political institutions and will resist any formal censorship. That is all well and good, but we still need to be concerned about self-censorship. The openness of science is integral both to its progress (addressed below) and to its authority among the public. This notion of "legitimate scientists" risks encouraging the notion that professional scientists are elitist snobs who want to rule over the ignorant masses, in part by keeping them ignorant. This type of move is very dangerous both for science and for democracy.

- Censorship can at best delay the independent development of this technology (10-20 years, I'd say). It also is likely to retard the progress of mainstream research into infectious diseases, with the extent dependent upon how well implement the system of access is. Regardless of the calculus here, the point is that we cannot stop technologies from spreading to our enemies, and the best strategy for protecting ourselves may paradoxically be to allow technologies to spread freely, while dedicating our resources on maximizing our own capabilities to respond to infectious diseases -- whether natural or engineered.

- The release of a pathogen like this new flu virus will probably be either ineffective or suicidal. Either the virus won't spread well and the outbreak will not expand, or it will expand rapidly and affect the entire globe. Anyone seeking to use it as a tool for "Clash of Civilizations" terrorism would be extremely foolish. While the terrorist may be able to inoculate himself and his close associates, the only societies that could engage in widespread inoculation are Western and Japan. So there would be some terrorists who may be able to use this weapon effectively, but they aren't our typical Islamist boogeymen (think: Unabomber, or White Supremacists)

Monday, December 12, 2011

The international post-humanist movement

I'm not gonna let them ostracize every group that disagrees with their bizarre belief system.

I'm getting sick of these skirmishes. I want to confront them directly, because I know that these stone-throwers can be defeated -- just like al Quaeda and its sympathizers can be. These movements are primitive, and are heading to the dustbin of history. I figure that the best way to neutralize them (and minimize the damage that they do) is to have them focus their hatred on a social movement that they have no hope of defeating. For that role, I propose:

Basically, the point here is to tell these barbarians that everything they hold sacred is a load of crap, and that we fully intend to leave them in the dust. We will tell them that all of their differences -- be them religious or nationalist -- are nothing compared to the difference between the post-humanist goal and everything that has come before. We embrace science and technology. We seek artificial intelligence, and we will happily become cyborgs. We will put all of their superstitions behind us, and realize a wonderful world of technophilic hedonism. We intend to become so powerful that they will be little more than ants to us, and their culture will only continue to exist due to our grace.

The problem is, we have only been drifting in this general direction, not seeking it whole-heartedly. There are a few organizations seeking to address the issues of our post-human future, but they do not engage in the culture war. Perhaps there is good reason -- maybe the idea of post-humanity is repulsive to most people. I just read Ian Bank's "Use of Weapons" (part of the Culture series), and I'm kinda jazzed about the possibility to live a pleasant life while simultaneously undermining these authoritarian movements.

I don't know what is the best strategy, but I expect that the conservatives will start attacking the transhumanist movement within my lifetime, as an ideal target for their politicized nostalgia. For now, I can rest knowing that technophilic hedonism is well established in our culture...

Sunday, December 11, 2011

All intellectuals should learn how to program a computer

Very quickly, society is becoming divided into two groups: those that understand how to code and therefore manipulate the very structure of the world around them, and those that don't – those whose lives are being designed and directed by those that do know how to codeI'll extend this, and assert that all intellectuals need to learn how to write programs. The gist of my argument is that we now have ready access to incredibly powerful tools for manipulating information. If you cannot use these tools, then you cannot manipulate information at the same level as your peers, and therefore you cannot participate in the modern intellectual community.

Personally, I have encountered many situations where a "philosophical" issue would benefit greatly from the sorts of calculations that computers can perform easily. Most notable is the demand for mathematical modelling or simulation: it often is not possible to fully explore the implications of your assumptions without explicit modelling. This applies to political philosophy and social theory just as it applies to biology. I have even seen students of the history of science who could have benefited from computer simulations -- for instance, some classic scientific texts (e.g. Galleleo's) describe experimental results that are inconsistent with modern scientific knowledge; historians may try to examine this issue by recreating the experimental conditions of the historical scientist, but this requires immense work and ends up being a guessing game. Computer simulations can examine the effect of possible confounds much more efficiently.

An added bonus of formal modelling is that it forces the thinker to be explicit about their assumptions, so it is a great aid to communication. Too often, philosophers (both amateur and professional) are just talking past each other.

So, my advice to all the young thinkers is this: if you want to learn how to think, learn how to program.

Update: I suppose that I should provide some tips on how to learn programming. Personally, I took a college level class, and then taught myself in the context of some projects I was working on, and I just picked up bits and pieces from different sources (another self-taught programmer, some books, and some websites). It probably was not the most efficient approach, but it worked well enough.

Right now, I can recommend two sources:

- Eclipse for Total Beginners (to learn Java)

- The Alice programming environment (a toy language for 3-D storytelling)

Saturday, December 10, 2011

All nations are invented

Anyway, the discussion of whether any particular nation was "invented" is kinda pointless, since nationality is intrinsically a myth. All nations are invented.

The "University challenge" -- decreasing costs; increasing access

Schumpeter: University challenge | The Economist

I don't have any particular comment on this, but one of the commenters at The Economist website brought up the "University of the People" which seems to be an establishment-backed effort to develop a model for low-cost online education.

Thursday, December 08, 2011

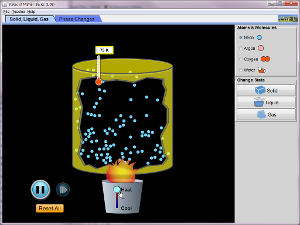

Physics simulations: ideal gas

As such, building awareness of new educational tools is key. In that spirit, I recommend PhET, which produces simulations to help instill an intuitive understanding of scientific concepts. The most recent simulation is pretty good... a simulation of transitions between states of matter, and also seems to demonstrate some aspects of the ideal gas law (i.e. PV=nRT). The only problem I noticed is that when the user increases the volume, thereby decompressing the substance, the temperature does not drop... or maybe it's been too long since I studied thermodynamics.

Anyway, check it out:

Sunday, December 04, 2011

Vegimite > Marmite

This confirmed my suspicions, Vegimite is better than Marmite, which explains why the Marmite never lived up to the high expectations that had been established by Vegimite. By smell, the Vegimite is more hoppy. I'll be evaluting the taste again in the near future... I'm so happy.

For you serious people, I am NOT turning this into a food blog.

In fact, I'm thinking that I'm going to focus much more on educational (and scientific) issues, as opposed to broader issues about power relations. I've got a bunch of topics that I want to address, but I'm slowed down by my long-windedness. If you've got any topic you want discussed, advice for how to approach this topic, or good blogs for me to check out, please leave a comment.

Thursday, December 01, 2011

Market Communism

That high quality allows Aravind to attract patients who are willing to pay market rates. Then it takes the large profit made on those surgeries to fund free and subsidized surgeries for poor people — like K. Karuthagangachi....On one hand, this is not all that surprising--American hospitals (and often lawyers) operate on a similar principle. My fear is that, like their American counterparts, these organizations may eventually turn into "profit-making" enterprises for their highly paid managers, while using their supposed "non-profit" status as a way of winning special privileges from the local community.

it's only possible to provide free surgeries on the scale that Aravind does by running an operating surplus, like a profit-making company. That's what Aravind manages to do, even though it's legally a charitable trust.

Anyway, this story shows the stereotypical Indian twist -- finding a way to radically reduce the cost of a service:

Fifteen years after it was founded, Aravind's ability to provide free and subsidized surgeries was being limited by the high cost and availability of the intraocular lenses needed for cataract surgery. That's not a problem most charitable organizations could overcome...This is a refreshing story showing how a "communist-minded" person can leverage "capitalist" processes to transform the lives of many who have been left out of the system. This isn't traditional philanthropy -- since the market service and the charitable service are intimately connected. We could even say that the charitable impulse came first, and the marketing impulse followed in its wake. The desire to help the poor inspired a business model that may not have occurred to a person who was only looking for profit. In contrast to the doctrinaire bickering that I always read on the web (touting the primacy of profit-driven capitalism or charity-driven communism), it is nice to see that in some situations, charity can drive advances in productivity and market savvy can help those who are incapable of helping themselves. Maybe there is hope for humanity.But Aravind attacked the problem with the help of an American social entrepreneur named David Green. Green had been helping Aravind collect donated lenses to be implanted in their cataract patients. But donations were averaging only about 25,000 a year. That wasn't nearly enough to meet Aravind's needs, and the lenses cost several hundred dollars to buy. So Green helped Aravind set up its own lens manufacturer on-site, a subsidiary named Aurolab.

"Now today Aurolab sells, I think this year it will be 1.8 million lenses," he says. "So you can see that when you have a business model, an economic model, it enables something to scale because it's not dependent upon charity, which is fickle."

And even more remarkable: By squeezing out profits made by middlemen in the production and distribution chain, Aurolab is now providing some lenses at the astoundingly low price of just $2.